Ascending Mount Iztaccihuatl

Mount Iztaccihuatl is a dormant volcano located about 40 miles east of Mexico City, Mexico. Standing at 17,159 feet, it is the third highest mountain in the country. It lays just north of Mexico's second highest mountain, the currently active Mount Popocatepetl at 17,820 feet. There is a rather involved legend that centers around the two volcanoes, but suffice it to say Mount Iztaccihuatl is said to resemble a sleeping woman and thus is sometimes referred to in Spanish as La Mujer Dormida. Given its close proximity to Mexico City, it appears to be frequently climbed, although I suspect only a small percentage of climbers reach the top. This blog entry is about my climb of Iztaccihuatl on February 20, 2016.

This is the license plate for the state of Mexico (not to be confused with the city

or country of Mexico). Mount Iztaccihuatl is seen on the left, just above the LXB.

- Elevation: 17,179 feet (third highest peak in Mexico)

- Elevation gain: 4,139 feet from base to summit.

- Distance: Nine miles round trip via the main trail.

After spending a free day at my own expense in Mexico City, our guide picked Susan and me up at our hotel in an old pick-up truck with bad suspension. Things were off to an ominous start as the guide immediately starting coughing straight into the palm of his hand. I didn't want to come off as a snobbish American with a lecture on hygiene, so kept my mouth shut. Said coughing continued non-stop, in the hand, for the entire week.

Visiting the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, where

the Virgin Mary allegedly paid a visit to Mexico.

The rustic Altzomoni Hut has three rooms with bunks and two bathrooms with no running water. You have to pour water from nearby barrels to flush the toilets. The facility is adjacent to other buildings behind a wire fence supporting several antennas. Spending a night at this high altitude was definitely a good way to acclimate.

The next day our schedule said we would hike up to the Refugio hut, which is about half way up the mountain. This seemed like a good idea, as it would break up our long hike at high altitude over two days. Plus, after spending a night at Camp Muir on Mount Rainier, I enjoy spending time in high-altitude shelters.

However, there was a change in the schedule for unexplained reasons. Our first full day of the program would involve going part of the way up the volcano and coming back down again, in an effort to acclimate better to the altitude. So, this we did, and it was a very easy day. We got back to the hut early, for we had a midnight wake-up call and needed to be in bed by 6:00 PM.

A problem bubbled up when preparing dinner before going to bed: a shortage of water. I recall the guide starting our trip with about 15 gallons of water, but apparently we consumed almost all of it already. As we bandied around ideas about what to do, another guide, from a competing service, and a guest came along. Despite having only one guest, this guide was well prepared with plenty of water. In the end, the other guide kindly gave our thirsty party of three some of his stash.

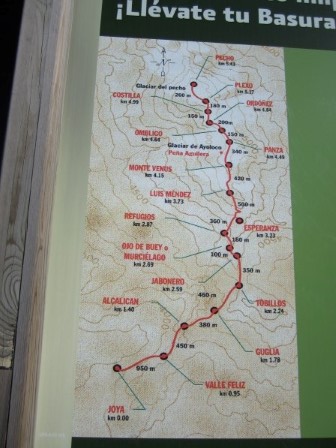

At midnight, we geared up, put our packs in the truck, and headed to the base of the trail, which is a parking lot known as La Joya (the jewel). There, we put on our head lamps and packs, grabbed our hiking poles, and headed up the same trail we traveled the previous day.

The beginning of the climb is a straightforward trail. As we climbed, our guide mentioned we had a long drive to the city of Puebla afterward and if we didn't reach the summit by 11:00 AM, we would have to turn around. This was of some concern as Susan was going slow compared to me. Compounding the problem was the fact that the guide wasn't wearing a watch. After asking me for the time, he suggested we keep going up slowly and reassess the situation when we reached the high Refugio hut.

The section before the hut is steep and slippery, due to loose rocks. They call it the jabonero (soap maker). You may wonder why. Who would be making soap way up here? It is a joke based on a Spanish rhyme: "En la casa del jabonero, quien no cae resbala." That translates to, "In the house of the soap maker, he who doesn't fall, slips. "

When we finally arrived at the Refugio hut at about 3:00 AM in the cold and wind, we encountered three other climbers getting ready to depart. After about half an hour they left and the hut was suddenly so nice, dark, and quiet. Then, despite having a strict schedule to keep, we all feel asleep. Somebody nicely left a Mexican blanket, which I used to keep warm, with my helmet as a pillow.

At one point, I woke up and suggested to the guide that we leave. He replied it was too cold and windy and we should wait until the sun comes up. Although I feared this would risk putting us too far behind schedule, I'm usually one to respect authority so I didn't question his plan. It is also true that high elevations tend to be windy the hour or two before sunrise. So, I curled up under my blanket and went back to sleep.

Later on, I woke up again in the total darkness of the hut, moved some window coverings out of the way, and noticed it was broad daylight outside. I woke up the guide and my friend so we could get moving. Indeed, it was a lovely, clear morning and the wind had died down significantly, as expected.

After a much longer than expected rest, we resumed the climb. Beyond the hut, what had been a trail became more of a route. I was in front and just followed the crowd of other climbers upward. Evidently, dozens of other climbers started later than us but skipped the nap in the hut. The next point of significance is the knees of the sleeping woman. Here, we took a short break. I believe it was at this point Susan declared that given the long break at the hut and her slower speed, she would never reach the summit by the turnaround deadline. She very kindly took one for the team and said I could go on with the guide and she would slowly go on at her own pace and meet us at some point on our way down.

The guide didn't seem enthusiastic about this idea. I think he was expecting I, too, would choose to turn around early, making his job easier. However, I was enthusiastic to give it my best shot and said that while I would respect the authority of the guide, I wanted to continue. The guide acquiesced to my enthusiasm.

Before going on, the guide said, "Mike, do you have any extra water? I left mine in the hut." Pause. The last guided climb I did was of Mount Rainier with the Rainier Mountain Guides. In my blog entry of that climb, I may have painted RMI too strongly as being slave drivers who timed everything to the minute and perfectionists about having all appropriate gear on a very long list, with water being one of the most essential items. At this point, I was sorely missing the RMI professionalism and good old reliable Pete, the lead guide of our group. If only he could see this.

Getting back to the request for water, I started the climb two liters. At the time of the request, I had about 1.2 liters left, spread between two one-liter bottles. Not wanting to increase my chances of being contaminated with whatever sickness was ailing my guide, I asked him, in English, if he had an empty water bottle I could pour some of my water into. He replied, "No." Keep in mind, I needed enough water to reach the summit and get all the way back to the parking lot. He only needed enough water to get to the summit and back to the hut to retrieve his forgotten water.

Common sense would dictate I pour most of my water into one bottle for myself and let him contaminate the other bottle. However, at high altitude, common sense does not always prevail. You have to experience high altitude to understand it. It's best described as your IQ dropping as the air gets thinner. As long as you're just marching forward, you don't really notice it, but you will notice it if faced with some kind of decision requiring logical thought. I know it seems stupid now, but I offered him my green water bottle, thus contaminating half my water, which he eagerly drank directly from and handed back to me to carry.

The next stretch is my favorite part of the climb as the route goes up and down the belly (panza), navel (obligo), solar plexus (plexo), and ribs (costilla) of the sleeping woman. Although the air was thin and windy, the views were fantastic. In terms of elevation, I was at an all-time high, by thousands of feet. Nothing in this section is especially steep or dangerous.

At our next stop, I offered the guide my green water bottle. As you may recall, even with my oxygen-deprived brain, I had the foresight to ask if he had an empty bottle I could pour water into, which he denied. As I pulled the water bottle out of my pack, he produced an empty plastic water bottle out of his. WTF! I specifically asked him if he had one and he said "no." In retrospect, I should have asked him in Spanish, which I could have done. Dang. Well, no sense crying over spilled milk, or contaminated water, so I poured enough water to see him back to the hut into his bottle. At least I wouldn't have to carry it now.

After crossing a knife-edged ridge with bellowing sulfuric fumaroles on one side, we reached a spot overlooking an ice field near the summit. To get to the ice field, one needed to descend a steep ledge, either on loose rock or ice. In retrospect, I should have put on my crampons and descended on the ice. I lugged the things all the way up and it would have been nice to make some use of them. However, the guide kept reminding me that we were short on time, so I foolishly chose to descend the steep and loose scree, self-arrest style. I went down a lot faster than I expected. It turns out the reason was the scree was actually just a thin layer of rock on top of ice. Fortunately, I made it down with only minor cuts on my left leg.

Crossing the ice field was fun. Then it was back uphill and a walk along another ridge line. Later, we came to another ice field. There were three high points around it, including the one where we stood. At this point, it was about 11:15 AM, about the time we should have reached the summit. However, were we at the top, known as the pecho (breasts) of the sleeping woman? I wasn't sure.

The only man-made item to mark our spot was a god's eye and a tea pot. A point across the ice field had two or three crosses on it. However, there were crosses all over this mountain, so that didn't necessarily mean much. The third point, which could be reached without touching ice, had nothing man-made on it. It is always nice to see a flag, survey marker, or register on a summit to mark the highpoint and make for better summit photos. Forgive me for stereotyping, but Mexicans are generally not shy about decorating and memorializing anything. Somehow, where we stood just didn't feel like a summit.

So, I did the obvious thing and just asked my guide, "Is this the top?" He paused and said, "Yes." However, the way he toned it, I didn't believe him. I wasn't sure if he didn't know or he knew the highpoint was across the second ice field and just didn't want to go there. Furthermore, if this was the top, where was the "congratulations!"?

Being an anal-retentive type, I explained to the guide that I wanted to reach the true tippy-top of Iztaccihuatl, even if it was just an inch higher than where we now stood. He gave me a look like, "Are you nuts? What difference does an inch make compared to a whole mountain?"

After some back and forth, we agreed to go to the easier-to-reach point to the left, the one that didn't require crossing the ice field. Surely, if we went to all three points we would reach the highest point, even if we didn't know which it was. So, we headed to the point to the left. The guide lagged far behind. When I reached the spot, my GPS indicated it was not as high as where we came from. When the guide caught up, he suggested we go back to the original point and if we were to go to the last remaining point, it would be easier to cross the ice field from there. That I agreed with.

When we got back to the original point, the guide said, "I'm not going to that last point. If you want to do it, I'll stay here and watch you." The ice field, and the lip above it, looked rather dicey. I've never known a guide to not accompany his guest in dangerous conditions, as opposed to relax and watch from afar. Then again, given everything else that happened that day, it didn't surprise me.

So, I pulled my crampons out of the bottom of my pack and affixed them to my boots, something I haven't done since Mount Rainier and I still have trouble remembering which one is the left and which is the right. As I was putting them on, another guide with one guest came along. He looked very knowledgeable and strong, so I asked him which point was the top. With all the gear he and his guest were wearing, I didn't recognize him. Turns out it was Pablo, the guide from the Altzomoni Hut who saved us from our water shortage the day before.

He said my question was a topic of frequent debate but according to his personal measurements, the point at which I stood was higher by five meters. This was great news! No longer would I have to cross a dangerous ice field by myself. With that, I whipped out my camera for the ubiquitous summit photos. I also warmly congratulated Pablo's guest, a woman from Sweden, who I got to know a little back at the hut.

Just as I was about to head down, a very handsome young man ran to the top in a running outfit with a Camelback pack. I went over and asked him how long it took him to reach the top, as he clearly clicked a stop button on his watch. He proudly said, "Two hours and fourteen minutes." I couldn't believe it. That surely put my ten hours to shame. Here are some pictures of him he kindly let me take. Enjoy.

As RMI always said, getting to the top is just half the battle. The first challenge in getting back down was getting back up through the ice field where I cut myself earlier. Here, too, I should have put on my unused crampons. However, I've climbed up scree too many times to count in my own mountains of southern Nevada. This didn't look that bad.

It was, however, bad. I truly learned during what looked like scree was just loose rock on top of ice. It took everything I had to get up it without crampons. Stupid! It would have been nice to have a professional offering advice in such situations. My advice to all readers reading this is to wear crampons in both directions through this ice field.

The struggle of sliding down 4 inches for every 5 I climbed really sucked a lot of energy out of me. It was nice to finally get back on solid, fairly flat ground, but the hike down was still very tiring for me. While I was the fastest going up, I was the slowest going down.

On the way down, we passed other guides from the same guide service. I asked one of them which was the true summit and quoted what Pablo said. The answer I got was, "Don't listen to (Pablo). The point with the crosses is the highest by two meters, but everybody recognizes the initial point as part of the top." Well, that wasn't what I wanted to hear, but as far as I was concerned I had done Iztaccihuatl. If anybody reading this can shed light on this summit mystery, please write me.

The rest of the slog down was slow and tiring. I've always been stronger going uphill than down, and on this day, I bit off more than I could chew to begin with. However, make it down I slowly did, thanks to plenty of ibuprofen.

It was then a long three-hour drive on mostly dirt roads to Puebla. The guide knew the name of our hotel but had no address or any idea how to find it. However, he asked for directions from people on street corners, taxi drivers, and police officers. We finally found the hotel at about 11:00 PM. What a long day.

Suffice it to say, I was disappointed with the guide and going crazy with his endless coughing. He was a very nice man who did his best. If he were in good health and had the experience of leading this trip a few more times, I think he would make an adequate guide. However, between being exhausted and having lost faith in him. I decided to walk away from the rest of my trip.

When I shared this decision with Susan, she agreed with me. We decided to blow off Orizaba and take some extra time to truly enjoy Puebla and Mexico City.

The guide company was very concerned about what happened and arranged to have the same guide take us back to Mexico City after a full day in Puebla, with a stop at the Teotihuacan pyramids on the way. Our guide was obviously very concerned for his job; he made our journey back to Mexico City an enjoyable one. He never once ask me why we chose to cancel Orizaba, probably not wanting to know.

Back in Mexico City, the guide service owner met with us and we relayed a sampling of our complaints. We were torn between being honest versus not wanting the guide to lose his job because of us. The company owner and his assistant, who were very helpful with the changed arrangements, were sympathetic. They agreed to pay for our extra hotel days in Mexico City, and they offered us a future trip.

I'm not going to disclose the name of the guide service, because I think they overall probably do a good job. Still, they have to own it for hiring a sick and inexperienced guide. If I had it all to do over again, I think it is worth the extra money to go with a company with high standards like RMI. They cost almost twice as much, but, like they say, you get what you pay for.

I don't rule out returning to Mexico to finish what I started. It would be a great trip to combine Pico de Orizaba, Nevado de Toluca, and La Malinche, the (1st, 4th, and 5th highest mountains in Mexico). I think I would employ the same guide service, assuming I got a more experienced guide, which I think they owe me.

By the way, I did indeed get sick after the climb. Obviously some gastrointestinal bug as evidenced by an acute case of Montezuma's Revenge and losing eight pounds. I hope you can tell from pictures of me, it isn't like I'm overweight to begin with. As I write this, I'm still fighting it, hopefully correctly, with a self-prescribed course of antibiotics.

Overall, I did climb one of the two mountains I set out to summit, and the more difficult of the two as I've been told. I had some fun times in Mexico City and Puebla, too. It may not have been a complete success, but it was certainly a memorable trip.

Update

After I returned I met Kurg Wedburg, founder of Sierra Mountaineering International and asked him about where the true summit of Iztaccihuatl was. As I feared, he said it was the far point across the ice field that I didn't go to. However, he added that difference in elevation between that point and where I turned around was within "spitting distance."

Here are links to a couple pictures Kurt took of the summit, taken in November, 2011:

Video

Please enjoy my video of the climb.